The beginning of Divine Right takes place over 40 years ago, and its continued popularity is a testament to the game's solid design, deep mythos, and great characters. Glenn shared his design notes and the fascinating history of Divine Right with us, so prepare to enter the turbulent world of Minaria from the very start. (Part 2 here.)

DR2: The 25th-Anniversary Edition

Divine Right lay fallow for a long time,

but the collector price grew appreciably—copies going for $200 apiece were not

unusual. A couple of possibilities developed for computer versions of DR,

but both fell through.

As of May 1994, Divine Right seemed to have a chance of rebirth with a game company

called Excalibre in Ontario, Canada. Its president called me, saying that he’d

been hearing for years how gamers wanted the return of Divine Right. He therefore inquired whether I was interested in a

DR reprint. I was very much interested, in fact, and said that I had a lot more

material that I had roughed out over the years and that might be worked into a

new edition. Revision and expansion sounded fine to Excalibre, and I was

encouraged to let my imagination run free. Thereafter, I worked off and on

(mostly on) for four years, coming up with an extensive expansion of both DR and

Scarlet Empire.

By late 1997, alas, it became clear that the

Excalibre project was not going to go ahead, and I saw no choice except to

terminate the contract as of late 1998.

While disappointed at the turn of events, the

time-consuming revision of DR that had ensued had not exactly been wasted. The

mythos of Minaria had become much richer with the introduction of many more

plot elements and characters. The work had been worth doing, and Ken and I at

least had a playtest copy that was fit to present to a publisher. In

retrospect, it’s hard to see how four years could have been better spent.

How true this was became clear in the first part

of 2001, when I received an unexpected call from Shawne Kleckner, president of

The Right Stuf International in Des Moines, IA. He wanted to know whether Divine Right was currently available for

republication. I told him that it was, pointing out that it had undergone a

good deal of revision over the last two decades. The upside of DR’s expansion

was that we could offer him the choice of publishing either the classic game or

the new updated version. Even though Right Stuf was a video-import house and

not a game company, Shawne had been fascinated by Divine Right from his first acquaintance with it and thought that

the game would be a good product for Right Stuf, as its long-awaited revival

would be a service to the game community.

Shawne called back a week later with a definite

offer. He wanted to call the Right Stuf publication the “25th Anniversary

Edition,” which at that time would be accurate only if one dated the design

from the earliest prototypes. Ken and I signed shortly after. We worked hard at

polishing rules to final form and in revising and expanding the Minarian

Legends. The game was printed and ready to ship by the end of 2001.

Over the next few months, the congenial Shawne

Kleckner and his sister, Kris, impressed us with their enthusiasm for the

project.

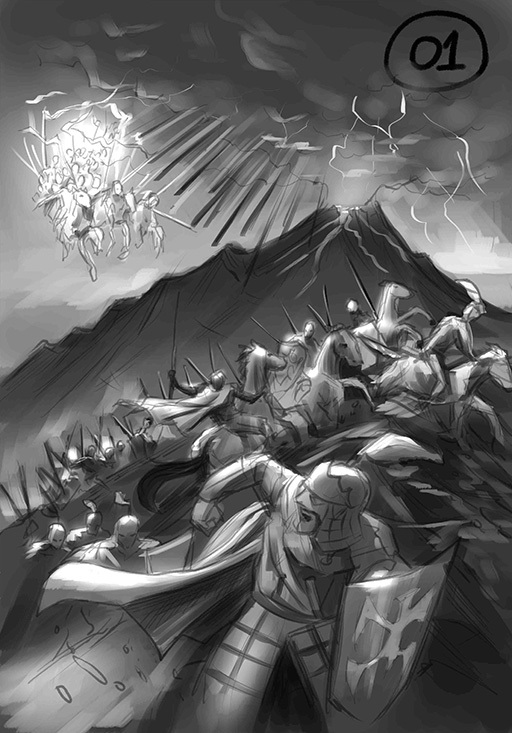

The Stormriders

Even while Ken and I were still working on DR2,

I had believed that Scarlet Empire

might never be published. I wanted fans who bought DR2, though, to have the

excitement of having the whole of Minaria engaged against a single powerful

foreign invader, even if this invader could not be the

Scarlet Witch King. It would be necessary for the invader not to have an

in-play hinterland of his own. I decided to use a sort of Genghis Khan-type of

intruder to stand in for the nefarious Scarlet Witch King.

My first choice for their name had been “the

Storm Bringers” or “the Flame Bringers,” but author Michael Moorcock had first

dibs on those names. While names, technically, cannot

be copyrighted, I had no reason to step on Mr. Moorcock’s toes. The first

fallback name for my marauders was “Stormriders,” a term that was used

variously in stories and movies and so seemed to be available for fair use. So

that is the name I used.

It was not hard to introduce faux Mongols into

DR2. Already I had worked out rules for a similar type, the Eastern Horsemen

(which remedied the lamentable lack of barbarians on that huge eastern border

of Minaria). These lesser barbarians were suggestive of the Huns, Turks, and

Magyars that perplexed Eastern and Central Europe in the Middle Ages before the

Mongol explosion.

Historically, the Mongols suddenly arrived as

strangers into Europe, as steppe nomads tended to do. They seemed bent on

savage war and conquest, although there had been no real causus belli and, up to then, no significant interaction between

the Continent and Mongolia. To guide the martial actions of the group that I

called “the Stormriders,” I adapted the rules already crafted for the Scarlet

Empire. They were moderately modified to fit the slightly different

circumstances. These borrowed rules are to be seen in particular in the

Minarian vassal rules.

The author looks forward to the continuing possibility of some future Scarlet Empire release. If current plans bear out, it is not impossible that the victorious Stormriders will clash at the borders of Girion with a primed and ready Scarlet Witch King, and two evil empires will send their elite minions and dejected vassals into monumental battles in many lands and climates.

DR2B

When DR2 arrived, Ken and I were surprised to

find that the product differed greatly from our design. Things had been changed

and added without the opportunity for the designers to advise. And the changes

had been bold and risky: some old DR1 rules had been restored without being

integrated smoothly with the rest of the rules as they stood after revision.

This resulted in the problems that were cited by some buyers. I offered an

errata to address the worst of the problems, and the Kleckners posted it on

their company’s website. The errata collection is considered to be the

DR2B edition, a supplement to what we thereafter would refer to as DR2A.

Another unfortunate aspect of the development

was that the recommended color scheme for the counters and map had not been

followed. The changes were not always aesthetically or practically pleasing.

Some of the new hues were printed too dark or too garish, as in the kingdoms of

Zorn (dark purple) and Pon (dark red). Another surprise was that Right Stuf’s

designers had decided to print all non-kingdom counters in black and white.

Also, the counter sheets were not die-cut but only perforated and not very deeply,

making it hard to get a good, clean separation.

On the other hand, Shawne had been interested in

the history of the design and included a CD that contained PDF files of early

game parts, as well as the complete Minarian Legends. Another feature of the CD

was printable archive files of all the counters, allowing the purchaser to

print quality replacements as needed.

While mistakes had been made in the DR2A

edition, the creators were determined not to let the perfect gainsay the good

and did all they could to support DR2B. At first, the publisher had hopes that

the market would support a release of the companion game, Scarlet Empire. Alas, due to apparent difficulties encountered by

The Right Stuf, on which I can’t elaborate because we were not well briefed on

this aspect of the project, the company decided that one game was enough. The

option on Scarlet Empire was allowed

to lapse quietly, and The Right Stuf made no request for its extension.

DR2C and DRX

Many fans were unhappy with the problem-ridden rules

of DR2A and even with the DR2B supplement. Stan Rydzewski, a fan with a flair

for technical writing, contacted me about doing a new edition of rules, one

that would include a few new counters I had belatedly come up with and the

graceful integration of the errata into the body of the rules. Also, for a

period of months, Stan asked many insightful questions that further improved

the game. The documents that came to be known as “Stan’s rules” were

posted on the Yahoo DR site in 2002. We consider that to be the DR2C

edition.

But DR2C had no index, so another fan of

considerable writing ability stepped forward, J. McCrackan. He added an

index and made additional suggestions for revision. I received an

individual copy, but this was just the groundwork for the full version of the

current DRX edition, which has been revised through the processing of thousands

of intelligent questions from J and other players. J also fully

reorganized the rules and introduced the labeling of optional rules by numbers

of hierarchical complexity—a good idea that makes rules consultation

easier. What’s more, many additional counters have been added to the game,

such as traitors, priests, jesters, and others. Some players are adamant

about sticking to DR1, but those who consider the sky the limit for the game

will value J’s rules, I have no doubt.

Elements of a Classic Game

As I have said, Divine Right has been called a classic. This is something every

designer wants to hear, but what goes into making a classic? At the outset,

Kenneth and I were simply looking to achieve a lively, playable,

fantasy-military system. By the indefinable chemistry of such things, we had

worked out a straightforward military-political-diplomatic engine that was able

to support both a subtlety of strategy and lots of rapid action. The system

also turned out to have a remarkable flexibility that allowed a large array of

special options to be introduced as add-ons. These options, such as the special

mercenaries and the magic items, convey much of the colorful and madcap spirit

of things Minarian.

Over the years, the designers have had time to

reflect upon those elements that have led to DR’s enduring popularity. It seems

to this writer that the most successful fantasy games are those that skillfully

distill the ideas presented by a imaginative novelist. SPI’s War of the Ring and Chaosium’s Elric! and Stormbringer are two such games. Worlds created specifically for

board games, by and large, have been famously disappointing. Avalon Hill’s Dark Emperor and White Dwarf’s Demon Lord, to name but two, offered

many characters and much magic, but they failed to engage the imagination.

SPI’s Swords and Sorcery, full of bad

jokes and patronizing apologies for the fantasy genre, suggested that SPI,

mostly a modern-armor company, was out of tune with a growing part of its

customer base. This base was being schooled in fantasy role playing and tended

to be attracted to the idea of mythic heroism. When such gamers found what

they were looking for, they responded well, and we still hear from

enthusiastic people who discovered Divine

Right at the close of the Seventies.

Why were there not more and better military fantasy board games? It seems that these were not the most market-successful kind. Why not? The publishers tended to blame the genre itself instead of their poor presentation of it. White Bear, Red Moon (retitled Dragon Pass and re-released by Avalon Hill) is a notable exception to the board-game-without-a-novel; in fact, it became the inspiration for a successful role-playing release, RuneQuest. The latter also was picked up by Avalon Hill. That Chaosium president Greg Stafford was a fantasy editor/writer in the semi-pros may not be irrelevant. A memorable fantasy board game has to be built like a good story, utilizing character, atmosphere, and situation.

Divine Right Games is proud to be part of the next chapter in the story

of this classic game with the forthcoming Divine Right classic collector's

edition.